As HSK learners progress through their studies, they often encounter pairs of words that seem identical in English translation but carry distinct meanings and usage patterns in Mandarin. These "synonyms" are one of the top common mistakes Chinese learners make.

Understanding these nuances is crucial for achieving high scores in HSK exams and for practical language use. In this article, we'll delve into three sets of commonly confused words, exploring their grammatical logic and providing examples to help you master these distinctions.

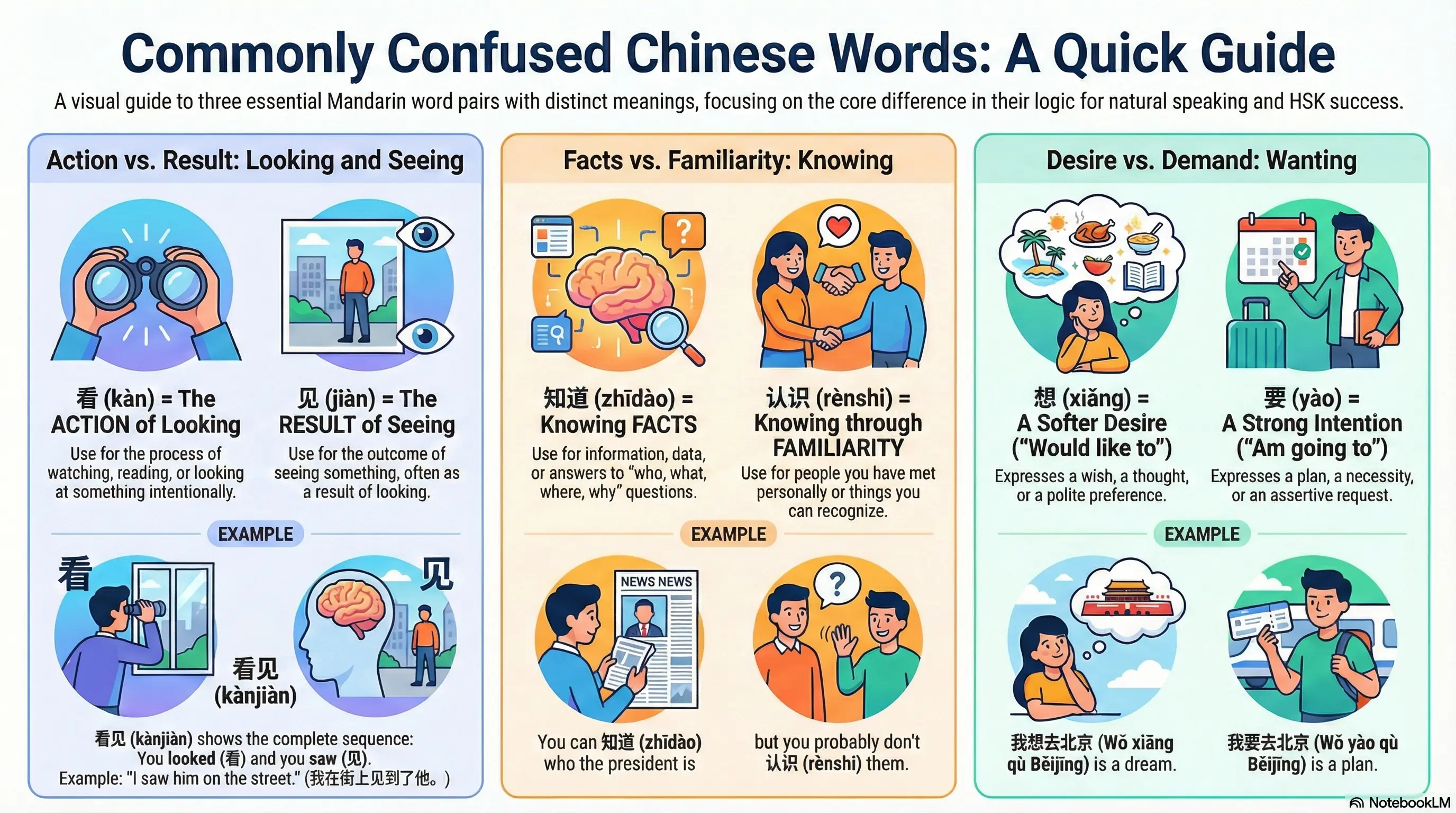

1. 看 (kàn) vs. 见 (jiàn): The Action vs. The Result

Many beginners struggle with the difference between "looking" and "seeing." In Chinese grammar, this distinction is often described as the difference between the action and the result.

看 (kàn): The Process of Looking

The character 看 (kàn) implies an active, voluntary effort to look at, watch, or read something. It focuses on the action itself, regardless of whether you actually spot what you are looking for. It is one of the most essential verbs in mastering Chinese verbs.

Key Points:

- Used for intentional viewing (watching TV, reading books).

- Often involves sustained attention over time.

- English equivalent: To look, to watch, to read.

HSK Vocabulary Examples:

- 看书 (kàn shū) - To read a book (process of reading)

- 看电视 (kàn diànshì) - To watch TV

- 看医生 (kàn yīshēng) - To see a doctor (visit for treatment)

In Context:

我每天都看新闻。

(Wǒ měitiān dōu kàn xīnwén.)

I watch the news every day.

Analysis: This emphasizes the habit and the action of watching.

见 (jiàn): The Result of Seeing

In contrast, 见 (jiàn) implies the result. You generally don't use 见 on its own to mean "look." It is often used in compound words or as a resultative complement to indicate that the visual input was successfully received.

Key Points:

- Used for chance encounters or the outcome of looking.

- Often implies a brief, momentary visual contact.

- English equivalent: To catch sight of, to meet.

HSK Vocabulary Examples:

- 见面 (jiàn miàn) - To meet (face to face)

- 再见 (zàijiàn) - Goodbye (literally: "see you again")

- 看见 (kànjiàn) - To see (Action "Kàn" + Result "Jiàn")

In Context:

我在街上见到了他。

(Wǒ zài jiē shàng jiàn dào le tā.)

I saw him on the street.

Analysis: This uses the particle "le" to indicate the completed result of spotting him.

2. 知道 (zhīdào) vs. 认识 (rènshi): Facts vs. Familiarity

Both words translate to "to know," but they are almost never interchangeable. This is a staple concept in HSK Level 2 vocabulary.

知道 (zhīdào): Knowing Facts

知道 (zhīdào) refers to having information in your head. It is about facts, news, answers, or situations.

Key Points:

- Used for factual knowledge (who, what, where, why).

- Followed by a clause or a fact.

- English equivalent: To know (a fact), to be aware of.

In Context:

你知道他是谁吗?

(Nǐ zhīdào tā shì shéi ma?)

Do you know who he is?

Analysis: You are asking for factual information about his identity.

认识 (rènshi): Personal Familiarity

认识 (rènshi) conveys a sense of familiarity or recognition. You use this when talking about people you have met personally, characters you can read, or roads you are familiar with.

Key Points:

- Used for people (acquaintances) or recognizing specific items (characters/roads).

- Cannot be followed by a "who/what/where" clause.

- English equivalent: To be acquainted with, to recognize.

In Context:

我认识他很多年了。

(Wǒ rènshi tā hěn duō nián le.)

I have known him for many years.

Analysis: This implies a personal relationship, not just knowing his name.

3. 想 (xiǎng) vs. 要 (yào): Dreams vs. Demands

These two words are often used to express "want," but the intensity and grammatical usage differ. They are both Chinese modal verbs that modify other verbs.

想 (xiǎng): Would Like To (Mental)

想 (xiǎng) relates to your mind (notice the "heart" radical 心). It expresses a desire, a wish, or a thought. It is softer and more polite than 要.

Key Points:

- Expresses thoughts, wishes, or "would like to."

- Can also mean "to miss" (e.g., 想家 - miss home).

- Tone: Polite, tentative, or internal.

In Context:

你想吃什么?

(Nǐ xiǎng chī shénme?)

What would you like to eat?

Analysis: Asking about preference or desire.

要 (yào): Going To / Need To (Will)

要 (yào) indicates a stronger intention or a necessity. It often implies that the action will happen (future tense) or must happen.

Key Points:

- Expresses strong desires, plans, or actual requirements.

- Can function as "going to" (immediate future).

- Tone: Assertive, determined, or urgent.

In Context:

我要一杯咖啡。

(Wǒ yào yībēi kāfēi.)

I want a cup of coffee.

Analysis: This is a standard way to order. It acts like a transaction: "I require/will take a coffee."

Comparison:

- 我想去北京 (Wǒ xiǎng qù Běijīng) = I would like to go to Beijing (it's a wish).

- 我要去北京 (Wǒ yào qù Běijīng) = I am going to Beijing (it's a plan/it's happening).

Conclusion: Mastering Nuances for HSK Success

Understanding the subtle differences between these pairs of words is crucial for moving from basic Chinese to intermediate fluency. As you prepare for your HSK exam:

- Context is key: Don't just memorize definitions; memorize sentences.

- Practice Resultatives: Focus on how jiàn attaches to kàn.

- Test Yourself: Try our HSK Mock Tests to see if you can spot which word fits in the blanks.

By mastering these nuances, you'll not only improve your exam scores but also sound more like a native speaker. Keep practicing, and 加油 (jiāyóu) — good luck with your HSK preparation!